The Cat Behind the OS: Meet the Real Mountain Lion

Wired Magazine (Brandon Keim)

It’s an oddity of consumer culture that nature is appropriated with little thought of the symbols being used. If Apple had named its latest operating system update after, say, the English longbow, the internet would be flush with stories about the Battle of Agincourt — yet barely a mention is made of actual mountain lions.

This just isn’t right. Mountain lions, or Puma concolor, aren’t just a branding device. They’re a reality, an evolutionary sculpture, an exquisite creature meriting the basic acknowledgement given the average Creative Commons copylefter.

“They’re the most successful land animal in the western hemisphere. They seem from an evolutionary standpoint to adapt to almost any situation, whether it’s the Amazon rainforest or the alpine habitats of the northern Rocky Mountains,” said Howard Quigley, director of the Teton Cougar Project at conservation group Panthera. “They must be doing something right.”

In that spirit, Wired presents some of the latest scientific developments in mountain lion research.

Florida Panthers

In the eastern United States, the only remaining population of mountain lions — also known as panthers, cougars, and by several dozen other names — live in southern Florida, where biologists and conservationists have fought to keep them alive.

Crucial to the effort has been the introduction of mountain lions from Texas, which gave a much-needed influx of fresh genes, keeping the Florida population from becoming disastrously inbred. For Linda Sweanor, who has studied mountain lions since 1985 and now heads the Wild Felid Research and Management Association, the Florida success is a symbol that transcends the state.

“It signifies whether or not we can have cougar populations into the future, because many places in North America are going the way of Florida,” Sweanor said. “If we can figure out how to keep them alive there, we can apply that information elsewhere.”

Florida Panther (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Are Mountain Lions Coming Back?

Until a few centuries ago, mountain lions ranged across the North American continent. Hunting by settlers exterminated many populations, but sightings in the central and eastern United States have occasioned speculation that mountain lions are making a comeback.

That’s not precisely what’s happening, said Sweanor. The cats are indeed roaming their ancestral lands, but they’re not settling down. They’re males searching for — and not finding — mates.

“There’s no evidence of any breeding populations outside the established populations,” Sweanor said. Yet while this might seem a dour take on a celebratory narrative of recovery, there’s a silver lining. Part of the reason why mountain lions are now seen roaming is because, thanks to conservation efforts, they’re surviving to do so.

A track in the snow in St. Croix county, Wisconsin (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

The Solitary Myth

That mountain lions are loners is an article of faith — a quick Googling returns “a solitary animal,” “solitary and stealthy,” “shy, elusive and solitary” — but isn’t necessarily true.

“One of the things we’ve discovered over the last few years is that they interact more than we ever thought,” said Quigley. “We found that males come and visit females with kittens. We even saw two family groups, females with kittens, sharing an elk kill. Then a male came along to hang out with both families. We assume he’s the father of both those litters.”

Mountain Lion Kittens (Linda Sweanor)

The Secret Life of Mountain Lions

Reclusive, largely nocturnal and possessing a hunter’s stealth, mountain lions are difficult for researchers to study without technological assistance. Radio collars have been invaluable in revealing their life histories and habits; at a more intimate level, motion-activated cameras provide candid, close-up glimpses that no human could ever obtain.

In the photograph below, a mountain lion uses a fallen tree as a scratching post, the first time such behavior was photographed.

(McBride & McBride/Southeastern Naturalist)

Roaming

While female mountain lions generally remain in the region of their birth, young males leave home and cross vast distances in search of mates. In one study of mountain lions in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the eastern edge of the species’ contemporary range, young males traveled an average of 160 miles from home; the longest journey was more than 600 miles, ending near Oklahoma City.

Even that voyage was a pit stop for another Black Hills mountain lion killed on a Connecticut highway in 2011. Subsequent genetic tests showed that hair and blood left at animal kills in Minnesota and Wisconsin belonged to that same lion, which ultimately roamed more than 1,800 miles.

(D.J. Thompson & J.A. Jenks/Ecosphere)

Living With Mountain Lions

In light of their fearsome reputation and symbolic role in America’s national psyche, it’s surprising to learn just how infrequently mountain lions attack people. Just 117 attacks were documented between 1890 and 2005, with a total of 19 deaths. Half of those attacks did, however, occur since 1991, a result of expanding populations among both mountain lions and humans.

To learn more about how mountain lions responded to people, Sweanor and colleagues regularly approached the great cats on foot during their studies, carefully documenting what happened and gathering results for a full 10 years. These were ultimately published in a study titled, with delightful reserve, “Puma responses to close approaches by researchers.”

“It was only the females with kittens where we had a threatening response,” Sweanor said. “It showed me how tolerant they are, and how there is potential for people and cougars to live alongside each other.”

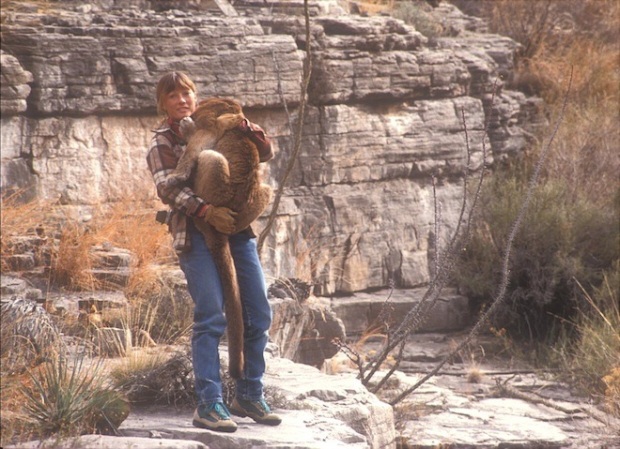

In the photograph below, Sweanor holds a tranquilized mountain lion in New Mexico’s San Andres mountains. Do not try this at home!

If You Meet a Mountain Lion

“It’s extremely rare that a mountain lion is ever going to look at a person as prey,” Sweanor said. “We do not have much to fear.” That said, it’s best not to be careless. In places where mountain lions live, Sweanor advised against hiking alone, especially at dawn and dusk, when the big cats are active.

“If you do encounter a mountain lion, then you want to group together. Pick up your children. You want to face the cougar. Never turn your back. Never run away,” she said. “If it starts to walk towards you, you want to look as big as you can. Don’t bend down. Don’t be lower than the animal. If it does attack, you’ll need to fight back.”

Sweanor recommended carrying a walking stick that in a pinch could be used in self-defense, and said she carries pepper spray while in the field. “But that’s more in case I run into an ornery person than for fear of a wild carnivore,” she said.

A mountain lion identified as F96 peers from its den in the San Andres mountains. (Linda Sweanor)

Smart Cats

Animals scientifically recognized as intelligent tend to be creatures amenable to laboratory experiments, such as chimpanzees and parrots, or routinely observable in nature, like elephants and dolphins. It’s a safe bet that a mountain lion will never be given a mirror self-recognition test — which doesn’t mean they’re not smart, but simply that they’re hard to evaluate with established protocols.

In unscientific terms, however, there’s an everyday source of insight into mountain lion intelligence that doesn’t even require seeing one. Just spend time with a housecat. “You can definitely extrapolate,” said Sweanor. “Cats are cats. There are so many behavioral similarities between cat species.”

(Travis Bartnick/Panthera)

Ecological Roles

The primal power of a mountain lion is viscerally obvious. Less immediately evident, but perhaps no less fundamental, is their ecological significance.

Large animals shape the world around them, altering flows of nutrients and disease and growth. By preying on deer, mountain lions keep the herbivores from becoming too numerous, which in turn prevents them from overgrazing a landscape and subsequently starving.

“Predators such as cougar probably dampen the oscillations,” Sweanor said. “Instead of having that rise and crash, having a cougar on top modulates things.”

The Meaning of Mountain Lions

Science aside, mountain lions are a potent symbol of life beyond the boundaries of our own species. “I have incredible respect for the large cats, for their power, their intelligence,” Sweanor said. “They’re survivors. They epitomize healthy, wild places. I can’t imagine a world without them.”